Resources for Designers, Contractors, and Inspectors

New Jersey Stormwater Best Management Practices (BMP) Manual

The New Jersey Stormwater Best Management Practices Manual (BMP Manual) is developed to provide guidance to address the standards in the state’s Stormwater Management Rules, N.J.A.C. 7:8. Revised or new chapters of the BMP Manual (Chapters 5, 12 and 13) available on NJDEP’s website.

The BMP Manual provides examples of ways to meet the standards contained in the rule. The methods referenced in the BMP Manual are one way of achieving the standards. An applicant is welcome to demonstrate that other proposed management practices will also achieve the standards established in the rules. The BMP Manual is developed by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, in coordination with the New Jersey Department of Agriculture, the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, the New Jersey Department of Transportation, municipal engineers, county engineers, consulting firms, contractors, and environmental organizations.

Read more

Municipal Stormwater Best Management Practices Construction Inspection Checklist

This checklist is meant for reviewing best management practices, including green infrastructure practices, during construction.

NJDEP Guidance Document: “Evaluating Green Infrastructure: A Combined Sewer Overflow Control Alternative for Long Term Control Plans”

This document provides guidance to combined sewer overflow (CSO) permittees within the State of New Jersey – that is, the 21 cities that have combined stormwater and wastewater systems – to evaluate green infrastructure as part of their required Long Term Control Plans (LTCPs).

In 2015, the NJDEP issued New Jersey Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NJPDES) CSO permits to 25 permittees that require, among other things, the development of an LTCP to address periodic sewer overflows. As part of the LTCP, the permittee must evaluate alternatives that will reduce or eliminate the CSO discharges, and develop a plan and implementation schedule. Green infrastructure is one of the seven specific CSO control alternatives that must be evaluated for the purposes of the LTCP. Chapter 3 (titled Green Infrastructure Implementation and Performance Monitoring) discusses the importance of performance monitoring with respect to green infrastructure implementation. While not specifically required by the CSO permit, performance monitoring is integral to assessing whether or not green infrastructure practices are performing as designed and understanding how information gained can be applied on a larger scale. The chapter outlines the development of performance criteria, performance monitoring at the site scale, monitoring and adjustments to hydraulic models, pilot projects, and adaptive management. Finally, the chapter describes community engagement and education for performance monitoring and provides case studies.

Read more

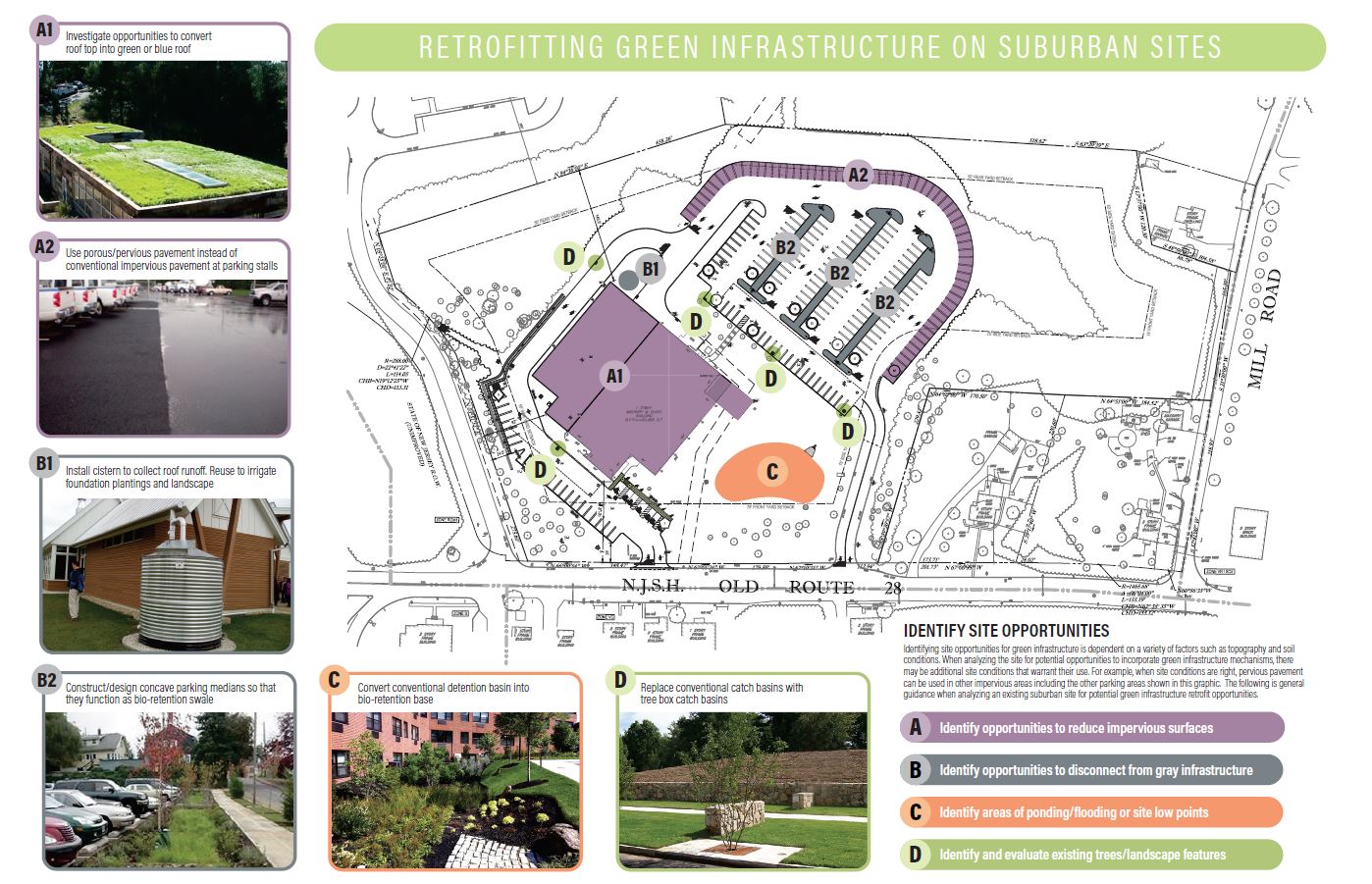

Green Infrastructure Guidance Manual for New Jersey

The manual, created by the Rutgers Cooperative Extension (RCE) Water Resources Program, provides a wealth of information for planning and design professionals, municipal engineers and officials, community groups, and inspired residents who are interested in installing green infrastructure practices to reduce the negative effects of stormwater runoff.

This manual provides users with information on the function and benefits of green infrastructure practices and technical design standards and describes the design process for a green infrastructure practice, guiding the user through the process from site identification to implementation. Using the details in this manual, stakeholders as well as design professionals that are planning to implement green infrastructure practices into existing development will understand the process from start to finish.

Read more

NACTO Urban Street Stormwater Guide

The Urban Street Stormwater Guide provides cities with national best practices for sustainable stormwater management in the public right-of-way, including core principles about the purpose of streets, strategies for building inter-departmental partnerships around sustainable infrastructure, technical design details for siting and building bioretention facilities, and a visual language for communicating the benefits of such projects.

“Green Infrastructure: “Coming to a Plan Set Near You” (Clay Emerson, ppt.)

New Jersey Future organized a panel on June 5, 2019 at the NJ Society of Municipal Engineers quarterly meeting where Clay Emerson presented on “Green Infrastructure: “Coming to a Plan Set Near You.”

“Porous Asphalt Pavement for Storm Water Management” (James Purcell, ppt.)

New Jersey Future organized a panel on March 14, 2017 at the NJ Society of Municipal Engineers quarterly meeting where James Purcell presented on “Porous Asphalt Pavement for Storm Water Management.”

Find Out More

Find Out More